The Bismarck Principle (Members Only)

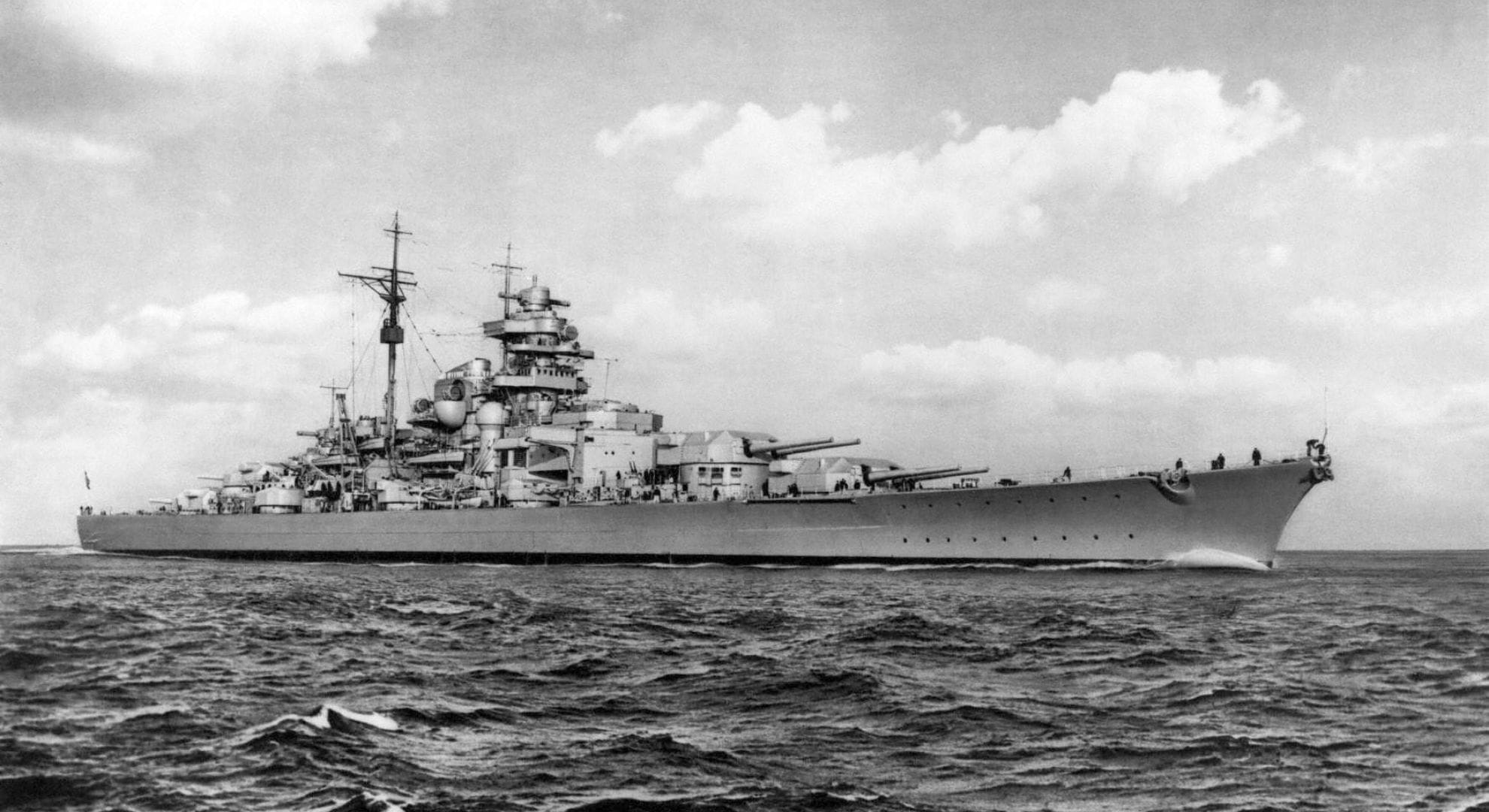

The battleship Bismarck lasted eight days.

Eight days from the moment it sank HMS Hood to the moment British torpedoes tore through its hull and sent 2,200 German sailors to the bottom of the Atlantic. The ship that was supposed to terrorize Allied convoys and dominate the seas became instead a hunted animal, desperately fleeing toward friendly ports while every available British warship converged on its position like antibodies attacking a virus.

This wasn't supposed to happen. The Bismarck was Nazi Germany's pride, a technological marvel that embodied the Reich's naval ambitions. At 50,000 tons, it dwarfed most Allied battleships. Its armor could withstand the heaviest shells. Its guns could sink any ship on the ocean. When it emerged from the Denmark Strait after destroying the Hood—Britain's most famous battle cruiser—the German crew must have felt invincible.

But invincibility became a curse. The Bismarck was too valuable to lose, too important to risk, and too threatening to ignore. These three characteristics created a perfect storm of strategic paralysis that would ultimately destroy not just the ship, but the entire German surface fleet strategy.

Where am I going with this?

There’s a simple idea that I want to lean on:

The Psychology of Irreplaceable Assets

Human beings make terrible decisions about irreplaceable things. We know this from behavioral economics: loss aversion makes us overvalue what we already possess, while the endowment effect makes us reluctant to trade away anything we consider "ours." Scale this up to institutions, and the psychological biases become strategic disasters.

The German naval command faced an impossible decision after the Bismarck sank the Hood. They could press forward with their original plan—raiding Atlantic convoys—but risking their premier battleship in the process. Or they could retreat to safety, preserving the ship but abandoning the mission that justified its existence.

They chose retreat. Admiral Günther Lütjens, commanding the Bismarck, received orders to abort the convoy raiding mission and make for the French port of Saint-Nazaire. The decision seemed rational: why risk the irreplaceable when you could preserve it for future battles?

But preservation became paralysis. By making the Bismarck too valuable to lose, German command stripped it of its primary purpose. A battleship that cannot engage in battle becomes an expensive symbol rather than an effective weapon. Worse, its very existence forces the enemy to adapt their entire strategy around neutralizing the threat.

The British response was swift and overwhelming. Every available ship in the Royal Navy—battleships, cruisers, destroyers, aircraft carriers—was redirected to hunt the Bismarck. The pride of the German navy became the focal point of British naval operations, drawing resources and attention like a massive gravitational well.

The Magnet Effect

This is what I call the Bismarck Principle: when a system creates something so vital it cannot be lost, that thing becomes a magnet for the exact forces that will destroy it.

The principle operates through three mechanisms. First, irreplaceable assets create strategic rigidity. Normal military doctrine accepts losses as part of operations—you trade casualties for objectives, sacrifice pawns to protect the king. But when an asset becomes irreplaceable, this calculation breaks down. Every decision must now account for protecting the irreplaceable thing, constraining your options and making your moves predictable.

Second, irreplaceable assets attract disproportionate enemy attention. The British didn't hunt the Bismarck because it was the only German ship at sea—dozens of U-boats posed a more immediate threat to their convoy routes. They hunted it because its symbolic and strategic value made its destruction a priority that transcended normal tactical considerations.

Third, irreplaceable assets become psychological burdens for their operators. The crew of the Bismarck knew they were aboard Nazi Germany's most important ship. This knowledge affected their decision-making, making them more cautious when boldness might have served better, more defensive when offense was required.

The result was a ship powerful enough to sink any opponent but psychologically constrained from seeking those fights. The Bismarck's greatest battles were fought while running away.

Corporate Cathedrals

Microsoft's Internet Explorer dominated web browsing for years, becoming so central to the company's strategy that executives feared any major changes might disrupt their market position. The browser became irreplaceable—too important to risk with aggressive updates or major architectural changes. This preservation instinct allowed more agile competitors like Firefox and Chrome to innovate around the edges, eventually displacing Internet Explorer entirely.

Companies build "cathedral" headquarters—massive, expensive facilities that become symbols of corporate identity. But these cathedrals often become strategic anchors, preventing companies from adapting to changing business conditions. The physical plant becomes too valuable to abandon, even when operational efficiency demands relocation or restructuring.

Kodak's film manufacturing infrastructure represented decades of investment and technical expertise. The facilities were irreplaceable in the sense that rebuilding them would cost billions and take years. This made digital photography feel like a threat to the company's core assets rather than an opportunity for evolution. The preservation instinct kicked in: protect the irreplaceable film business at all costs.

We know how that ended.

The Innovator's Dilemma, Weaponized

Clayton Christensen's "Innovator's Dilemma" describes how successful companies fail to adapt to disruptive technologies. The Bismarck Principle offers a complementary perspective: companies create their own disruption by making certain assets so important that they become strategic liabilities.

The mechanism works through misaligned incentives. When something becomes irreplaceable, organizational energy shifts from using it effectively to preserving it indefinitely. Managers optimize for asset protection rather than mission accomplishment. Innovation slows because changes might threaten the irreplaceable thing.

Meanwhile, competitors face no such constraints. They can experiment freely, take risks, and adapt quickly because they have nothing irreplaceable to lose. The preservation instinct that constrains the incumbent becomes the disruptor's greatest advantage.

This engineers a a perverse competitive dynamic: having the best assets becomes a disadvantage when those assets become irreplaceable. The company with the most to lose moves most cautiously, while companies with less to lose move more boldly.

Systems that become irreplaceable often become ineffective.

The German Tiger tank faced similar problems during World War II. These massive armored vehicles were technological marvels—nearly invulnerable to Allied anti-tank weapons and capable of destroying any Allied tank. But they were also expensive, complex, and difficult to replace. German commanders became reluctant to risk them in combat, using them defensively rather than exploiting their offensive capabilities.

Allied tanks were individually inferior but collectively more effective because they could be risked, lost, and replaced. The Sherman tank wasn't better than the Tiger - not by a long shot - but Sherman crews could take risks that Tiger crews couldn't afford.

The Nuclear Exception

Nuclear weapons are an interesting exception to the Bismarck Principle. These are literally irreplaceable in the sense that using them destroys them, yet they remain strategically valuable precisely because they cannot be used.

The deterrent effect of nuclear weapons depends on their preservation. A nuclear weapon that could be safely expended would be less effective at preventing conflict than one whose use carries enormous consequences. In this case, irreplaceability becomes a feature rather than a bug.

But even nuclear strategy shows traces of the Bismarck Principle. Countries with smaller nuclear arsenals often face pressure to preserve their weapons rather than use them for deterrence. The calculation changes when you have twelve nuclear weapons versus twelve thousand—each individual weapon becomes more precious and harder to risk.

Escaping the Trap

- First, recognize that irreplaceability is often an illusion. The Bismarck seemed irreplaceable because German naval planners had invested so much in battleship technology. But U-boats were actually more effective at disrupting Allied shipping—the original strategic objective. The irreplaceable asset was less important than it appeared.

- Second, build redundancy deliberately. Systems with multiple critical components are more resilient than systems with single points of failure. This requires accepting some inefficiency in exchange for strategic flexibility.

- Third, maintain the willingness to sacrifice important assets for strategic objectives. This sounds simple but requires fighting against loss aversion and organizational politics. Someone must have the authority to risk irreplaceable things when the mission demands it.

- Fourth, question whether assets are truly irreplaceable or simply expensive to replace. The distinction matters because expensive things can eventually be rebuilt, while truly irreplaceable things create permanent strategic constraints.

The Modern Bismarck

What are today's battleships? Which assets have become so important that they constrain the organizations that created them?

In technology, we see companies trapped by their own successful platforms. Social media companies built algorithms so central to their business models that changing them feels impossible, even when those algorithms create obvious social problems. The preservation instinct kicks in: protect the irreplaceable algorithm at all costs. Hardware and software companies are no better off - observe Apple in 2025.

In finance, certain banks became "too big to fail"—irreplaceable components of the economic system. This irreplaceability created moral hazard, encouraging risky behavior because the institutions knew they would be preserved regardless of performance. Hence, the GFC.

In infrastructure, we see cities trapped by transportation systems too expensive to replace but too outdated to serve current needs. The preservation instinct prevents adaptation, even when the infrastructure no longer serves its original purpose effectively. Which explains why New York’s subway system is decrepit and in decline.

Beyond Preservation

The Bismarck sank because German naval strategy prioritized preservation over purpose. The ship was designed to hunt, but was constrained from doing so because losing it seemed unacceptable. This constraint made the ship vulnerable to exactly the kind of coordinated attack that preservation was supposed to prevent.

The lesson isn't that powerful assets are inherently dangerous—it's that treating any asset as irreplaceable creates the conditions for its destruction. Organizations that build Bismarcks must be prepared to risk them, or they will inevitably lose them to more flexible competitors.

The principle applies whether we're talking about battleships, feeds or iPhones. When preservation becomes the primary objective, effectiveness becomes secondary. And when effectiveness becomes secondary, preservation becomes impossible.

Germany built something so powerful they were afraid to use it. Eight days from glory to grave, destroyed both by enemy action and, inevitably, by the impossible burden of being irreplaceable.

The hunters became the hunted the moment they decided they had too much to lose.

Discussion