The Privacy Paradox: Why We Don't Practice What We Preach

We say we value privacy. So why the fuck do we keep giving away our data? It’s more complicated than you think.

As a journalist and tech fan, I’m relatively “passionate” about privacy; I attend conferences, I do the reading and I write blog posts and essays about the importance of protecting personal information. In short, I know the damn assignment.

But then I reach for my phone to check my social media feed, and before I even think about it, I’ve granted a new app access to my contacts, location, and photo library. Seriously, it’s almost pathological.

And my behavior isn't an anomaly. Believe me, I’m not that fucking special.

It's the privacy paradox – the glaring disconnect between our stated preferences about privacy and our actual online behaviour.

The Paradox Unveiled

In 1978, long before we all became chronically fucking online, a privacy researcher named Alan Westin began conducting surveys that would shape our understanding of privacy attitudes for decades to come.

Westin's work, spanning over a quarter-century, categorized people into three groups based on their privacy concerns:

- Privacy Fundamentalists (about 25% of the population): These individuals are highly concerned about privacy and resistant to sharing personal information.

- Privacy Pragmatists (about 57%): This group weighs the benefits and risks of sharing information on a case-by-case basis.

- Privacy Unconcerned (about 18%): These individuals have little to no concern about privacy and freely share personal information.

These categories seem to offer a neat explanation for people's varying online behaviors. But here's where things get interesting: even many of those classified as "Privacy Fundamentalists" readily shared personal information when put to the test in experimental settings.

This discrepancy became even more pronounced with the rise of social media in the early 2000s. A 2006 study by researchers Alessandro Acquisti and Ralph Gross found no significant relationship between individuals' stated privacy concerns and their actual information disclosure on Facebook.

It's as if we're all living in two parallel universes: one where we vehemently defend our right to privacy, and another where we willingly hand over our most personal information for the slightest convenience or social reward.

The Numbers Don't Lie

If the privacy paradox were a rare occurrence, we might be tempted to write it off as an interesting but inconsequential quirk of human behavior. But the statistics tell a different story.

A 2017 survey in Australia found that 69% of respondents were more concerned about online privacy than they had been five years earlier. But this heightened concern didn't translate into meaningful action for most. It's like watching a group of people express growing alarm about a approaching storm while steadfastly refusing to seek shelter.

Even more telling is an experiment conducted with 46 Saudi Arabian participants. When shown evidence of how their data was being harvested, their privacy concerns skyrocketed. But for the majority, this newfound awareness didn't lead to any significant change in behavior. It's as if they had been shown a map of quicksand but decided to keep walking the same path anyway.

The paradox isn't limited to any particular age group or demographic. However, there are some intriguing generational differences. A recent Cisco survey found that 42% of consumers aged 18-24 exercise their data rights, compared to only 6% of those 75 and older.

But while younger consumers are more likely to take action to protect their privacy, they're also more likely to engage in behaviors that put their privacy at risk.

The Anatomy of a Paradox

So why does this paradox exist?

Why do we consistently fail to practice what we preach when it comes to privacy?

Why can’t we get it together?

Part of it is a simple lack of understanding. Giving a shit about privacy doesn’t mean people grasp the actual risks and dangers associated with sharing personal information online.

Then there’s the skills gap. Even when folks are fully aware of the potential risks and threats to their personal data – hacking, phishing, spoofing – they just aren’t equipped to safeguard their information. They don’t understand how or why to set strong passwords, use encryption tools, take on board secure browsing practices or - more terrifyingly - question AI voice cloning etc.

For all the mandatory training and lunch ‘n learn seminars (wank), the skills gap isn't limited to the general public. We’re seeing it in organizations, where employees simply do not have the energy, the interest or the motivation to implement and maintain robust security measures. The result? Vulnerabilities that are going to be exploited by cybercriminals. It’s not if, it’s when.

Unlike tangible goods, the value of privacy is abstract and hard to quantify. How much is your browsing history worth? What's the dollar value of your location data? Without clear answers to these questions, it's easy to undervalue privacy in the face of immediate benefits or conveniences.

And that’s honestly the most insidious factor: the power of immediate gratification…

The Behavioral Economics of Privacy

Behavioural economists call this present bias, our tendency to overvalue immediate rewards at the expense of long-term benefits. When it comes to privacy, the rewards of sharing information (like social connection or convenience) are immediate and tangible, while the costs (like potential data breaches or loss of autonomy) are distant and abstract.

It ties into the notion of hyperbolic discounting – our tendency to choose smaller, immediate rewards over larger, delayed ones. In the context of privacy, this might manifest as choosing the immediate convenience of using a free app over the long-term benefit of maintaining control over our personal data.

The status quo bias – our preference for the current state of affairs - leads to privacy inertia. Changing privacy settings or adopting new, more secure behaviors requires way too much effort and it disrupts our routines. It's just easier to stick with the default options, even if they don't align with our stated preferences.

Finally, we can't ignore the role of social proof. When we see the folks in our friends list, in our feeds freely sharing personal information online, it normalizes the behavior- and it makes us more likely to follow suit, no matter what our stated preferences might be.

The Myth of the Rational Consumer

For years, policymakers and businesses have operated under the comfortable and oh-so-convenient assumption that consumers make rational decisions about their privacy.

But the privacy paradox throws a wrench in this logic. If people aren't acting in accordance with their stated preferences, can we really trust them to make rational decisions about privacy?

This dilemma has given rise to two competing arguments. The "behavior valuation argument" suggests that people's actions reveal their true (low) valuation of privacy, implying that less regulation is needed. On the other hand, the "behavior distortion argument" contends that people's behavior is distorted by various factors, including cognitive biases and manipulation by companies.

Professor Daniel Solove of George Washington University Law School takes this a step further, arguing that the privacy paradox itself is a myth based on faulty logic. He contends that we can't generalize from specific instances of information sharing to conclude that people don't value privacy overall.

Solove's argument highlights an important point: privacy decisions are context-dependent. People might be willing to share certain information in one context but fiercely guard it in another. The challenge lies in creating systems and policies that can accommodate this nuanced reality.

Bridging the Gap

So, what’s next? How do we close the gap between what we say about privacy and how we actually behave online?

It’s not just up to us as individuals—we can and should make better choices, but our track record isn’t on our side. And in the absence of better consumer decisions, companies and policymakers have to step up. Businesses need to make privacy a core part of their DNA, not just an afterthought or marketing tool.

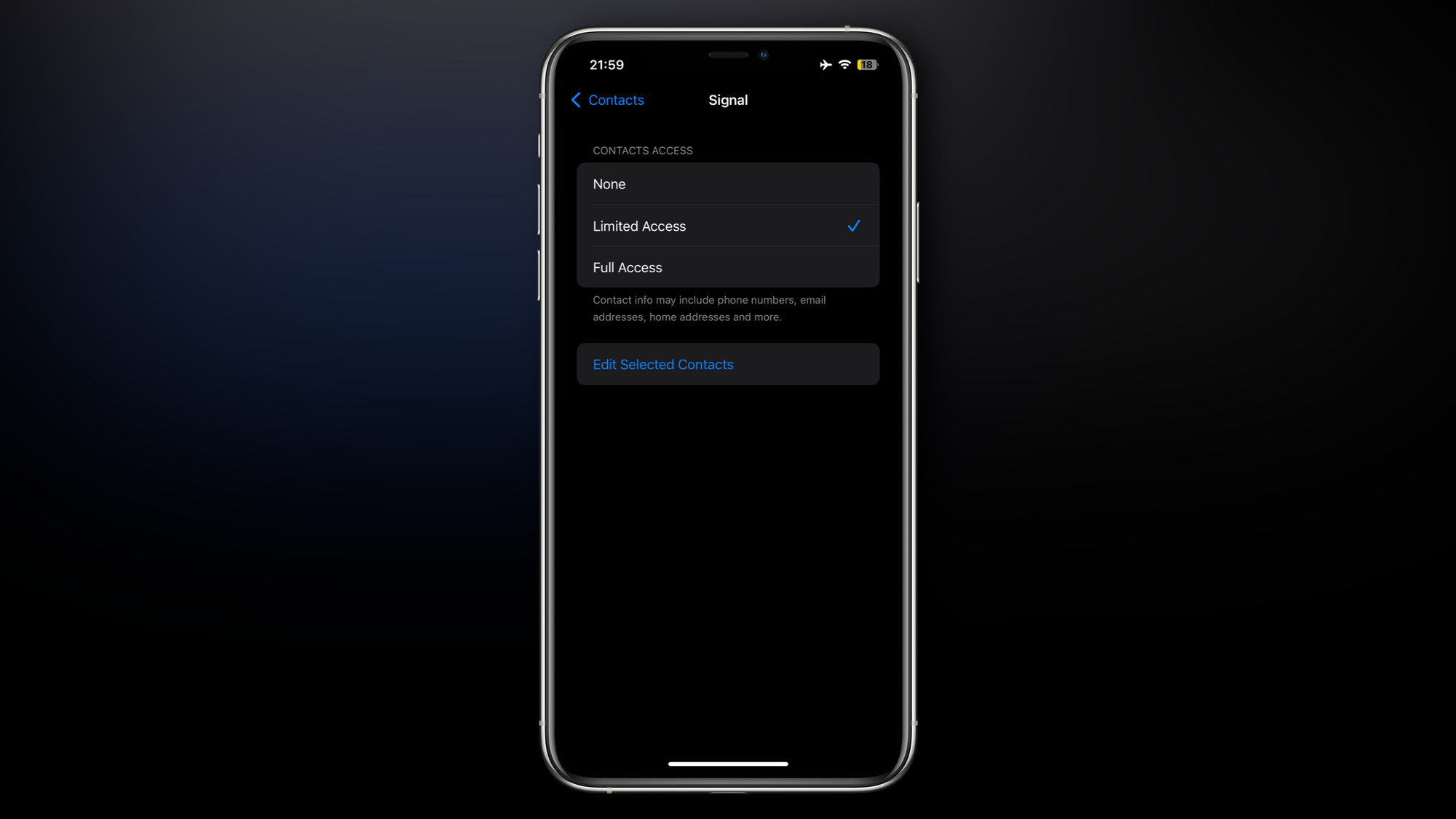

This means building products that protect user data by default, giving people real control over their information, and earning trust through clear communication. Apple’s move to restrict app access to contacts is a step in the right direction, even if the pushback shows how much further we need to go.

On the policy side, regulations have to catch up with the reality of digital life. Lawmakers should craft rules that protect our data, and rethink outdated concepts of consent and data ownership. The stakes are too high to settle for anything less.

The real privacy threat isn’t just from data-hungry companies or hackers—it’s our own willingness to trade our future security for a moment of digital convenience.

Discussion